Il rosso dell’uovo

The heart of the matter

Intervista ad Andrea Camilleri

Qual è stata la priorità che l’ha guidata nella direzione artistica della rassegna “Suoni di versi. Catania e le Città del Mondo”?

In passato ho provato più di una volta quasi un senso di ribrezzo nel veder rappresentati spettacoli estivi all’aperto, con le loro brave scenografie dipinte e costruite, perché spesso il risultato finale dell’allestimento che avevamo progettato, appariva letteralmente ‘contro’ l’architettura delle facciate retrostanti. Per quanto riguarda invece l’esperienza catanese, prima ancora di avere dei testi in mente da far recitare e da mettere in scena, sono andato direttamente sui luoghi. Così sono stati proprio alcuni luoghi di Catania, a suggerirmi le strade per raggiungere certi testi. Ad esempio, il Don Giovanni in Sicilia di Vitaliano Brancati, è un romanzo quasi totalmente ambientato in via Etnea, così ho proposto di far chiudere la via e di farlo rappresentare proprio lì, in mezzo ai passanti. Lo stesso è accaduto per Le Città del Mondo di Elio Vittorini, messo in scena nel Cortile Platamonte, e per tutti gli altri spettacoli in cartellone ad eccezione de La Messa della Misericordia, l’unico testo nato e pensato esplicitamente per il teatro, e dunque allestito nel sagrato della splendida Chiesa S. Niccolò l’Arena. Credo che Michael Nymann, direttore della sezione musicale dell’evento, in fondo, abbia fatto lo stesso mio percorso, valutando che alcune musiche non potevano assolutamente concordare con l’architettura e l’atmosfera della città. Così abbiamo lavorato di comune accordo in questa direzione.

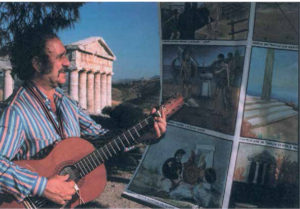

Nino Friscia. The storyteller’s paintings

Quasi sempre il pretesto alle trame dei suoi romanzi è un episodio, apparentemente marginale, dell’integrazione siciliana all’unità d’Italia. Se vi sono, quali sono le altre costanti?

In effetti, la maggior parte delle storie narrate nei miei romanzi sono ambientate nel periodo immediatamente successivo all’Unità d’Italia, un momento storico che mi sta particolarmente a cuore. Generalmente c’è una notizia che leggo, un fatto storico che mi colpisce e da cui traggo ispirazione. Tuttavia, non definirei le mie opere dei veri e propri romanzi storici, ma delle microstorie che prendono solo uno spunto dagli avvenimenti, poiché al di là di una suggestione iniziale, raccolgo pochissime informazioni e mi documento minimamente su quanto è realmente accaduto. Quando mi trovo a scrivere una storia che trova il suo pretesto in un fatto di cronaca, la mia scrittura procede in modo singolare: l’episodio che mi ha colpito, e da cui parto, è come il rosso dell’uovo: la zona centrale attorno alla quale, per cerchi concentrici, costruisco l’intero romanzo. Quindi la stesura non procede affatto, cronologicamente e linearmente, dal primo all’ultimo capitolo. Così il nucleo originario, che è stato il punto di stimolazione iniziale, non è detto che occupi la parte centrale del corpo narrativo definitivo: può darsi infatti, che la scrittura non si sviluppi in forma di cerchio ma di ellisse, e che quindi il punto di partenza si trovi, nella collocazione finale, ampiamente decentrato rispetto all’architettura dell’intero romanzo. Certamente così non ottengo una cronologia temporale perfetta, ma è proprio un’alterazione del tempo narrativo ciò che mi interessava sperimentare in un romanzo come Il birraio di Preston, dove gli episodi narrati parallelamente, si svolgono in realtà in tempi diversi. Addirittura La concessione del telefono è un mio tentativo di eliminare totalmente il narratore, lasciando il lettore solo, di fronte a lettere, documenti e brani di dialogo. Ma se nei romanzi del cosiddetto ciclo storico, mi sono permesso di effettuare una certa ricerca strutturale, mi sono voluto confrontare anche con quel genere di romanzo che lo stesso Sciascia riconosceva come l’unico in grado di ricondurre lo scrittore ad una rigida ingabbiatura logico-temporale: il romanzo giallo. È stata dunque una scommessa con me stesso, cominciare a scrivere La forma dell’acqua, il mio primo romanzo giallo. Ha rappresentato una sorta di autodisciplina personale, scrivere partendo proprio dal primo capitolo e seguendo un preciso ordine cronologico, senza alterare in nessun modo tempi logici e tempi narrativi: il giallo ti obbliga a non barare.

Nino Friscia. The storyteller’s paintings

Il suo stile contempla spesso il paradosso della battuta, il dialogo vivo e una intitolazione dei paragrafi che funziona come conclusione, posta in testa anziché in coda, della storia narrata. Caso esemplare di una simile struttura narrativa Il gioco della mosca (1995), all’apparenza una sorta di dizionario delle sentenze e dei detti siciliani, che si rivela in realtà una raccolta di storie cellulari. Si tratta di una strategia funzionale al recupero di fatti e fattacci esemplari, tradizionalmente affidati alla sola trasmissione orale?

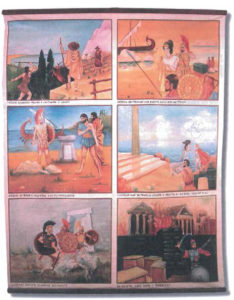

Quasi tutte le vicende narrate nei miei romanzi mi vennero raccontate. Ricordo quando al mio paese arrivava il cantastorie che, intonando una sorta di nenia fortemente ritmata, raccontava dei fatti di cronaca illustrandoli con dei disegni naïf, che nel corso della narrazione venivano indicati di volta in volta con una canna. Ecco, la mia ambizione è assolutamente questa: essere un moderno contastorie, cioè colui che racconta una storia, e la racconta pubblicamente, come era al mio paese. In effetti c’è dentro di me prima di scrivere, una sorta di racconto orale, che precede e determina la struttura di quanto andrò a scrivere. E subito dopo aver scritto una pagina avverto la necessità di rileggerla, avendo possibilmente almeno un ascoltatore. È proprio dal ritmo della mia stessa lettura che decido se modificare quanto scritto, tanto che una pagina spesso viene corretta anche quattro o cinque volte, ma sempre dopo averla letta almeno una volta ad alta voce. In effetti credo che i miei romanzi siano molto adatti ad una lettura ad alta voce, fatta anche a terzi, piuttosto che a una lettura privata. Ma oltre all’attenzione per l’aspetto orale, credo di conservare anche una certa sensibilità alla narrazione sinestetica. Del resto ho cominciato a scrivere il mio primo romanzo abbastanza tardi, quando avevo già quarantatré anni, e alle spalle una preziosa esperienza di comunicazione visiva, avendo lavorato per il cinema e per la televisione. Indubbiamente mi son portato appresso anche una certa esperienza nella caratterizzazione dei personaggi e nel dialogo, che trova origine soprattutto nel mio lavoro di sceneggiatore e regista teatrale. Sul palcoscenico il personaggio si presenta da sé: non c’è l’autore a descriverlo. E trovo che anche i dialoghi presenti nelle mie pagine siano una diretta presentazione e caratterizzazione del personaggio, il quale potrebbe funzionare anche se io non lo descrivessi affatto, come ho voluto sperimentare ne La concessione del telefono.

Ma nelle pagine dei suoi romanzi viene citata anche la rete di deliranti adempimenti burocratico-amministrativi e di decreti ministeriali, sciorinati senza soluzione di continuità dalla politica centralizzante della capitale. Nei testi da lei riportati leggiamo divertiti, tassonomie improbabili e intricate dissertazioni. In che modo un simile codice linguistico poteva comunicare il sistema di valori della nuova patria e dialogare con la comunità siciliana?

Non comunicava in nessun modo, trattandosi di due culture, e quindi di due linguaggi, completamente diversi. Caso esemplare è l’esistenza di dizionari per il gioco del lotto, credo unici in Italia. Infatti, se l’ufficiale statale del banco del lotto non era siciliano, era veramente impossibilitato a comprendere le richieste degli avventori e quindi doveva ricorrere a simili dizionari, consultando la doppia traduzione siciliano-italiano di parole, numeri da giocare e puntate. Il burocratese era un codice assolutamente autoreferenziale e come linguaggio dello Stato non entrò affatto in comunicazione con la comunità siciliana. È un dato di fatto che la politica post-unitaria abbia condotto un vero e proprio genocidio culturale, amministrativo ed economico nei confronti dell’isola, ma è pur vero che questo è accaduto anche con la complicità degli stessi siciliani, che non si sono mai sottratti a questa sorte. Quando fu introdotta la leva obbligatoria la maggior parte dei giovani non poteva ottenere l’esenzione dal servizio pagando, come fece invece Giovannino Verga, che provenendo da una famiglia ricca non andò mai a fare il militare. Così venivano sottratte alla produzione agricola le forze di lavoro migliori, tanto che i familiari e gli amici accompagnavano la recluta al distretto militare rigorosamente vestiti in nero, come per un lutto. Gli effetti dell’introduzione della leva obbligatoria furono immediati: il grafico delle nascite registra in quel periodo un crollo clamoroso, e nasce proprio allora quel bellissimo proverbio che è ‘nni livaru u piaciri do futtiri’ (ci hanno tolto il piacere di fare l’amore, avere figli, allevarli). Sia chiaro che non sono assolutamente contrario all’unità d’Italia, in quanto risultato di un’evoluzione ineluttabilmente scritta nella storia. Del resto è doveroso ricordare che gli stessi siciliani votarono quasi all’unanimità per l’unità, e non certo a favore della proposta di federazione. Ma sono i modi e i metodi dell’unità che sono stati assurdi e che poi si sono risolti in un boomerang, producendo quella che oggi viene definita ‘emergenza’ del Mezzogiorno. Perché il Sud non era così povero, allora.

Nel suo ultimo romanzo La mossa del cavallo, il registro dialettale siciliano si scontra ancora una volta con l’incomprensibile burocratese statalista, mentre l’italiano corrente appare incapace di tradurre la forma mentale e la tradizione culturale dell’isola, tanto che il protagonista, emigrante ormai settentrionalizzato, potrà addentrarsi nei misteri di un vero e proprio giallo paesano, soltanto dopo aver recuperato l’uso della propria ‘lingua madre’. Alcune realtà possono rivelarsi come precise strutture di senso, soltanto attraverso un particolare sistema linguistico?

Proprio così, le parole possiedono una loro ‘verità’. E credo che in sostanza, questa sia la tesi del mio ultimo romanzo. Il carattere puramente emozionale e forse ancestrale del dialetto è pienamente espresso in Giovanni Bovara, il protagonista, che pur essendo cresciuto a Genova dove ha imparato l’italiano ed il dialetto del posto, riesce a riappropriarsi della propria identità siciliana, dopo aver risvegliato in sé, attraverso momenti di grande intensità emotiva, quella che era la lingua dei padri. Questa sarà la sua mossa vincente, che gli consentirà di svelare tutta la verità sul crimine di cui è ingiustamente accusato. In effetti si tratta di un concetto che Pirandello aveva già magnificamente espresso alla fine dell’Ottocento in alcuni saggi sul linguaggio dialettale e la lingua italiana, osservando che, se di una data cosa il dialetto ne esprime il sentimento e l’emozione, la lingua italiana della medesima cosa ne esprime la ragione e il concetto. Da questa idea io mi sono mosso, dilatandola. Ma nelle ultime pagine del romanzo, ho voluto inserire un mio divertito, e spero anche divertente, modo di concludere la storia, come a dire: attenzione figli miei, stiamo dibattendo tra formiche, perché esiste una comunicazione superiore che trascende questo problema, quella dei grandi scrittori di ogni tempo e di ogni luogo, quella che cito e di cui faccio manbassa nell’ultimo capitolo, il Catalogo dei Sogni.

The storyteller Antonio Tarantino. Photo by Antonio Palazzolo

La lingua letteraria appare come un codice a cui la tradizione ha assegnato ormai larga autonomia espressiva. Contrapponendo i diversi assi e registri linguistici, in un gioco continuo di separazione e sovrapposizione, la sua scrittura mette in discussione, o quanto meno riesamina, l’identità del ‘linguaggio letterario’?

Senza dubbio. Ancora una volta desidero affermare la mia ambizione a voler individuare una voce tutta mia, di moderno contastorie. E chiamo voce questo mio particolare modo di scrivere, perché sono convinto che l’unica autentica possibilità di creazione per un narratore, e quindi per uno scrittore, sia quella dell’individuazione di una propria voce, che non può essere evidentemente quella di cui si serve nello scrivere un biglietto d’auguri o di condoglianze. Credo che la voce del canto di un tenore non sia la sua voce abituale, così come la voce dello scrittore non è la lingua omologata o la stessa lingua letteraria, che di per sé ha già un suo alto rischio di omologazione. La lingua dello scrittore deve attingere da fonti autentiche, essere una lingua viva, continuamente rinnovata.

[english]

Interview with Andrea Camilleri

By Maurizio Rossi

What was your priority in planning the artistic direction of the review “Suoni di versi. Catania e le Città del Mondo”?

On more than one occasion, I had felt a certain revulsion, almost, in seeing open-air summer shows with their nice, painted, constructed scenery, because often the final result of our set design seemed literally to clash with the architecture of the surrounding façades. On the other hand, as far as the experience in Catania was concerned, I went to see the sites first, even before I came up with the works to be acted and staged. So how to get at certain texts was suggested by the locations themselves in Catania. For example, the Don Giovanni in Sicilia by Vitaliano Brancati, a novel which is set almost entirely in Via Etnea. I suggested closing off the road and staging it there, among the passers-by. The same thing happened with Le Città del Mondo by Elio Vittorini, staged in the Cortile Platamonte and all the other performances, except La Messa della Misericordia, the only text conceived explicitly for the theatre, and thus staged in the parvis of the splendid Chiesa S. Niccolò l’Arena. I think Michael Nyman, the musical director, arrived at the same conclusion, basically; he felt that certain music could by no means come to terms with the architecture and atmosphere of the city. Thus, in working together, we were in agreement about this.

The pretext for the plot of your novels is almost always an apparently marginal episode taken from the integration of Sicily into a unified Italy. What are the other constants, assuming that they exist?

It is true that most of the stories narrated in my novels are set in the period immediately following the unification of Italy, a moment which I am particularly fond of. On the whole, it springs from something I read, an historical fact which strikes me and from which I draw inspiration. However, I wouldn’t really define my works as historical novels; they are microhistories, in a way, which spring from events. Apart from an initial suggestion, I gather very little information and I do very little reading on what actually happened. When I find myself writing a story which is inspired by a real event, my writing proceeds thus: the episode which struck me, my starting point, is like the yolk of an egg, the middle bit around which I build the entire novel in concentric circles. Therefore the writing does not at all follow on chronologically; it’s not linear, from the first to the last chapter. Thus the original nucleus, the initial stimulation, does not necessarily occupy the central part of the definitive narrative body. Indeed, it might be that the writing does not develop in the form of a circle, but in that of an ellipse and therefore the starting point, in the final arrangement, is to be found widely decentralised, with respect to the architecture of the entire novel. Of course, I don’t achieve a perfect temporal chronology this way, but in a novel like Il birraio di Preston, it was precisely an alteration of the narrative time that I was interested in experimenting – where the episodes narrated are parallel but they really happen at different times. La concessione del telefono was an attempt at totally eliminating the narrator, leaving the reader alone, with letters, documents and bits of dialogue. In the novels of the so-called historical cycle there was structural research behind what I was doing but I also wanted to try out that type of novel which Sciascia himself acknowledged as the only one which leads the writer towards a rigid logical-temporal cage: the detective story. So it was a gamble with myself, writing La forma dell’acqua, my first detective story. It was a sort of self-discipline, starting with the first chapter and following a precise chronological order, without altering logical and narrative time sequences in any way: you can’t cheat when you write a detective story; it won’t let you.

Your style is often a contemplation: the paradox of the remark, the dialogues and the paragraph headings which functions as a conclusion, placed at the beginning rather than the end of the story. An example of this type of narrative structure is Il gioco della mosca (1995), seemingly a type of dictionary of Sicilian maxims and sayings, which turns out, in fact, to be a collection of cellular stories. Is this is a strategy aimed at recalling certain events and foul deeds, traditionally entrusted to oral transmission?

Actually, almost all the happenings in my novels came to me in an already narrated form. I remember when the storyteller arrived in my village, chanting a sort of heavily stressed nenia (lament), he recounted events, illustrating them with naive drawings, pointing to them one at a time with a stick, during the narration. You see, my ambition really amounts to this: to be a modern storyteller, i.e. the man who tells a story, and tells it publicly, as it was in my village. In actual fact before I begin writing, there is sort of oral story already inside me which precedes and determines the structure of that which I will go on to write. And immediately after writing a page I am aware of the need to reread it, possibly with at least one listener present. It is the rhythm of my own reading which allows me to decide if I want to alter what I have written, so much so that a page is often corrected even four or five times, but always after having read it at least once aloud. Yes, I think that my novels lend themselves very much to reading out loud, to other people as well, rather than reading to oneself. However, apart from the oral aspect, I think I have preserved a certain sensitivity for synaesthetic narration. Actually I began writing my first novel quite late on, when I was 43, with a valuable experience of visual communication to build on, having worked for cinema and television.There’s no doubt that I had also brought along a certain experience in characterisation, in the characters themselves and in dialogues, which basically derived from my work as scriptwriter and theatre director. On the stage, it is the character who presents himself; it is not the author who describes him. And I find also that the dialogues present on my pages are a direct representation and characterisation. The character functioned even if I didn’t describe him at all. This was the case in La concessione del telefono.

But in your novels we also see the bureaucratic-administrative ravings and ministerial decrees of the centralising policies of the capital being paraded nonstop. In the texts you relate we gleefully read of improbable taxonomies and intricate theses. In what way could such a linguistic code communicate the system of values of the new homeland and converse with the Sicilian community?

It didn’t communicate in any way, seeing as it concerned two cultures and thus two completely different languages. An example is the existence of dictionaries for the lottery, the only ones in Italy, I think. The state official responsible for the lottery office was not Sicilian so he couldn’t understand what the customers wanted and therefore had to rely on such dictionaries, looking up the double Sicilian-Italian translation of words, numbers to bet on and stakes. Bureaucratic jargon was an entirely self-referential code and as a state language was not by any means capable of communicating with the Sicilian community. We know for sure that post-unity policies brought about an authentic cultural, administrative and economic genocide with respect to the island. However, it is also true that this happened also with the complicity of the Sicilians themselves, who never really went out of their way to avoid it. When conscription was introduced, most of the young men were not able to obtain exemption by payment, like Giovannino Verga who came from a rich family and therefore did not do military service. Thus, the best of the workforce was taken away from agricultural production, so much so that family and friends accompanied the recruit to the recruiting centre, rigorously dressed in black, as if in mourning. The effects of conscription were immediate: the birth rate fell dramatically in this period and it was then that the splendid proverb appeared: “nni livaru u piaciri do futtiri” (they have robbed us of the pleasure of making love, having children, bringing them up). Don’t get me wrong, I’m not at all against the unity of Italy, in that it was the result of an unavoidable evolution written into history. And we should point out that it was the Sicilians themselves who voted almost unanimously for unity, and not indeed in favour of the proposal of a federation. But the methods used to achieve it were absurd, they and boomeranged, in fact, leading to what is today called the ‘emergency’ in the Mezzogiorno. Because the South was not so poor at the time.

In your latest novel La mossa del cavallo, the Sicilian dialect register clashes once more with the incomprehensible state bureaucratic jargon, whereas modern Italian seems incapable of translating the mental form and the cultural tradition of the island, so much so that the main character, a Sicilian emigrant who is by now northernised, can only penetrate the mysteries of an authentic rural intrigue, after he has recovered the use of his own ‘mother-tongue’. Can certain realities only be revealed as precise sense structures through a particular linguistic system?

Exactly. Words possess a ‘truth’ of their own. And I believe that, essentially, this is the idea behind my latest novel. The purely emotional and perhaps ancestral characteristic of dialect is fully expressed in Giovanni Bovara, the main character, who, even though he has grown up in Genoa, where he has learned Italian and the local dialect, is able to get his Sicilian identity back, after awakening in himself, going through moments of great emotional intensity, that which was the language of his ancestors. This is the winning move which will allow him to reveal the whole truth about a crime he is unjustly accused of. This was, in fact, a concept which Pirandello had brilliantly discussed in a number of essays on dialect and the Italian language, written at the end of the 19th century. He observed that, while dialect expresses the sentiment and emotion of a given fact, the Italian language expresses the reasoning and concept behind it. I took up the idea from there and extended it. But in the final pages of the novel I wanted to insert something which amused me and, I hope it amuses others, to conclude the story, as if to say “just a minute folks, let’s not make a mountain out of a molehill, because a higher communication exists which transcends this problem, that of the great writers of all times and places, that which I quote and of which I make the most of in the last chapter, the Catalogo dei Sogni.

Literary language seems a code which tradition has assigned large expressive autonomy to. Setting the linguistic axes and registers against each other, in a continuous game of separation and superimposition, does your writing call in question, or at least re-examine the identity of “literary language”?

Yes, undoubtedly. Once more, I would like to stress my intention, which is to single out a voice which is all mine that of a modern storyteller. And, indeed, I define this particular way of writing I have, as a voice, because I am convinced that the only real possibility of creation for a narrator, i.e. a writer, is that of finding his own voice, and obviously this cannot be the same one we use to write a letter of greetings or condolences. I believe that the voice of a tenor when he sings is not his usual voice, just as the voice of the writer is not the ‘approved’ language or even literary language, which itself runs a serious risk of becoming ‘approved’. The language of a writer has to draw on authentic sources, it has to be alive as a language, continuously renewed.

(Tratto da/from: NB. I linguaggi della comunicazione, Shake the wor(l)ds, N.1, Anno II, Logo Fausto Lupetti Editore, Milano 2010.)