Annales

Il Duemila che ormai si approssima avrà molti eventi da celebrare a cominciare dalla fine del millennio (e poco importa che la data esatta sia il 2000 o il 2001), per passare al Giubileo, e alla fine di un secolo XX che già da solo ha molti motivi per essere celebrato. Forse le occasioni sono fin troppe se persino il teatro alla Scala, nella sua stagione bimillenaria ha deciso di rievocare il percorso dell’opera del Novecento, scordando apparentemente che, nell’anno che viene, ricorre anche il quarto centenario della nascita del melodramma: anniversario, se si crede agli anniversari, della massima importanza soprattutto per l’Italia e che invece sarà assai poco festeggiato, certo meno del centenario del Milan A.C.

Poco celebrata, a giudicare dalla mancanza di qualsiasi preparativo, sembra che finirà con l’essere anche una attività caratteristica di questo secolo che si chiude e che, se è stato certamente il secolo della comunicazione, è stato altrettanto il secolo della pubblicità.

Anzi, gran parte dello sviluppo dei mezzi di comunicazione, dalla radio alla stampa giornalistica, dalla televisione a internet è stata ed è tuttora finanziata dalla pubblicità commerciale, o dalla comunicazione aziendale, come oggi si ritiene più politicamente corretto dire.

Che questa particolare branca della comunicazione abbia profondamente interagito con la cultura del Novecento, sia a livello popolare che a livello alto, è innegabile.

Ha trasformato l’aspetto del paesaggio, soprattutto urbano e soprattutto della parte più moderna dei centri urbani; ha condizionato sin dal loro nascere i linguaggi televisivi sottomettendoli a palinsesti che devono innanzitutto tener conto delle inserzioni e delle interruzioni pubblicitarie; ha rivoluzionato la struttura e l’aspetto delle riviste; ha modificato, arricchendolo da una parte e impoverendolo dall’altra, il linguaggio quotidiano; ha influito sulla narrazione cinematografica in un rapporto di dare e avere di difficile analisi; ha contribuito pesantemente, anche se spesso inconsciamente, alla riscoperta della retorica (altro merito del secolo che muore); si è fatta arte popolare, ricevendo dalla cultura ufficiale quello stesso atteggiamento di interesse curioso e distacco spregiativo che altre forme di arte popolare – dal feuilleton al poliziesco, dall’avanspettacolo al fumetto – avevano già conosciuto; ha profondamente trasformato, creando anche non indifferenti problemi etici e giuridici, le pratiche della propaganda politica; ha contribuito sostanzialmente allo sviluppo e al progresso delle ricerche sociodemografiche e psicografiche e della psicologia sociale; è diventata arma formidabile per lo sviluppo della società dei consumi. E si potrebbe andare avanti a lungo in questo che non vuole essere un elenco di meriti, ma solamente un richiamo a quanto la pubblicità abbia cooperato in questo secolo a fare della nostra società quello che essa è oggi, per il bene o per il male.

La mancanza di celebrazioni corrisponde d’altronde ad un’altra lacuna: non esiste ancora una autorevole ed esaustiva storia dello sviluppo della attività pubblicitaria, dai primi reperti pompeiani alla vera e propria esplosione del nostro secolo. I motivi possono essere molti.

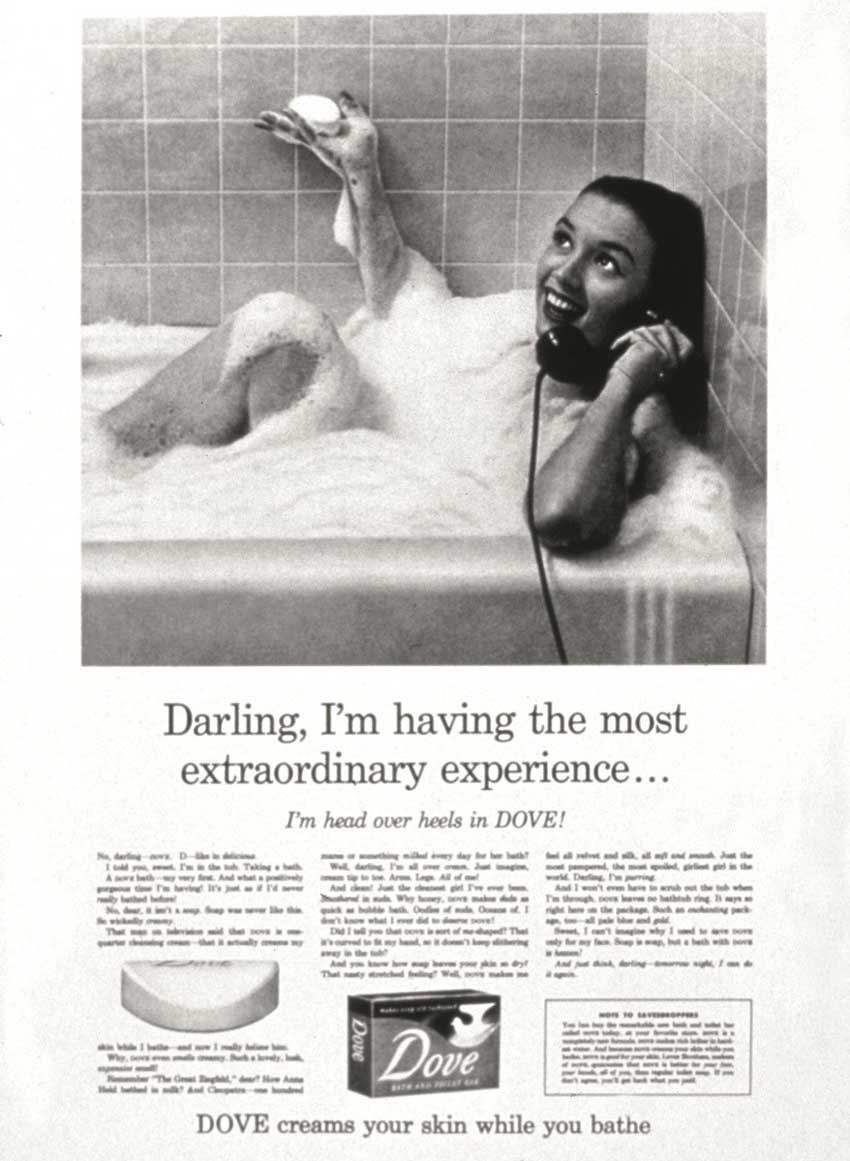

Da una parte si può pensare, come fanno alcuni degli stessi pubblicitari, che si tratti di materia del tutto inadatta alla storicizzazione. Quella pubblicitaria sarebbe una produzione effimera per natura, finalizzata a rispondere ad esigenze del qui e dell’oggi e destinata a scomparire non appena quelle esigenze siano superate. Che cosa interessa oggi sapere come la Camel accompagnasse l’affermazione del femminismo e quindi del fumo femminile, o sfruttasse l’affetto dei familiari dei soldati sui fronti della seconda guerra mondiale? Oggi tutto questo è lontano, la Camel deve far fronte a ben altri problemi e questi riguardano solo i suoi attuali comunicatori. Le vecchie pubblicità sarebbero a questo punto solo degli indizi utili a indagini sulla vita quotidiana di altri tempi, o tutt’al più, materiali di studio per addetti ai lavori e per gli studenti delle proliferanti scuole e università di comunicazione, come le arringhe degli avvocati del passato nulla dicono oggi al di fuori dell’ambito strettamente professionale.

I più estremisti arrivano sino ad aggiungere che la pubblicità non sarebbe neanche degna di una storia come arte minore1, poiché tale non è. È chiaro in questa posizione così negativa, che ancora una volta è sostenuta soprattutto dai pubblicitari, l’intento più o meno dichiarato di rivendicare alla propria attività se non una scientificità, almeno una prevalenza della tecnica professionale finalizzata al raggiungimento di un risultato pratico di tipo persuasorio, in cui la componente equivocamente spacciata per artistica altro non sarebbe che una serie di espedienti retorici da inserire al massimo in repertori e manuali. La sola storia possibile sarebbe dunque una storia delle tecniche pubblicitarie e del loro rapporto con l’evoluzione della teoria della comunicazione (ma anche in questo campo ben poco si è fatto).

Dall’altra parte occorre fare i conti con difficoltà non indifferenti nel reperire materiale, che possa essere di base documentaria ed esemplificativa a questa ipotetica storia universale della pubblicità. Difficoltà che sono principalmente legate alla scarsezza dei documenti dei secoli passati e alla eccessiva quantità dei documenti del nostro secolo (non per nulla gli esempi storiografici che abbiamo sono quasi tutti legati al Novecento e ad episodi particolari). Nei secoli passati sono state compiute imprese altrettanto titaniche in altri campi, ma tali fatiche sembrano basilarmente contrarie allo spirito e alle abitudini di oggi e il dubbio che ne valga veramente la pena non è certo adatto a stimolare gli eventuali esploratori.

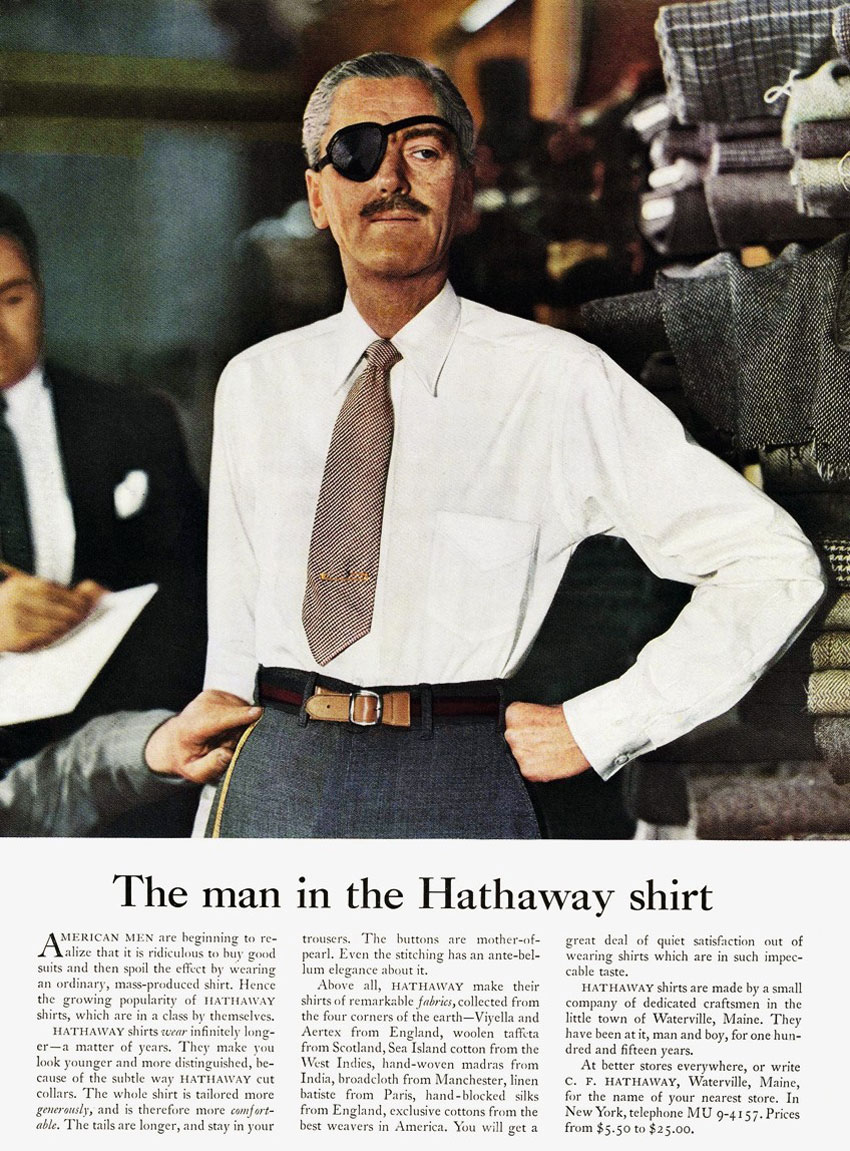

Va anche considerata la problematicità di decidere la scelta di un taglio, peraltro necessario per dare ordine e giustificare la presenza o l’assenza di determinati materiali. Che cosa si privilegerà: il lato estetico, provocando le reazioni dei pubblicitari più attaccati alla funzione persuasoria? Il lato innovativo, dando origine a una esposizione elitaria che trascurerebbe la grandissima maggioranza della produzione reale? Il lato economico, rinunciando a una grande quantità di episodi di scarso interesse commerciale, ma di alto interesse culturale? Chi avrà maggiore diritto ad entrare in questa storia, il commercial Ferro China Bisleri in cui per la prima volta in Italia e forse nel mondo si vide un uxoricidio con tanto di sparo e sangue e che è stato programmato pochissimo perché, rifiutato dalla Rai, trovò ospitalità solo nei cinema, o l’ennesimo presentatore che convince l’ennesima massaia a scegliere il suo detersivo e che viene programmato fino all’esaurimento, conquistando così una gran fetta di share of mind? Si darà diritto di accesso al mitico Michele che, criticato da tutti, decretò il successo del suo whisky e iniziò una nuova maniera di considerare l’intera categoria merceologica, o piuttosto al famoso comico genovese che con alcuni divertentissimi spot fece perdere quote di mercato al suo yogurt? O sarà la celebrità a determinare un criterio di selezione, secondo cui però un David Ogilvy finirebbe con l’avere la meglio su un Howard Luck Gossage, estremamente più sottile e innovativo di lui? Probabilmente la maniera più convincente di fare una simile storia – se mai si decidesse di farla – sarebbe quella di lasciarsi guidare dalle teorie che passo passo hanno guidato la produzione e le sue trasformazioni e di scegliere gli esempi fra quelli che meglio e più chiaramente esemplificano tali teorie.

Anche qui sarebbe comunque necessario, ma molto più facile, un discrimine fra le false teorie, dettate spesso solo da un bisogno metapubblicitario e autocelebrativo, e altre teorie conosciute solo ai più attenti fra gli addetti ai lavori ma che sono realmente alla base di gran parte della produzione di un’epoca. E bisognerà così rimettere al giusto posto una star-strategie e rivalutare in pieno le attitudes di Fishbein2.

E bisognerà non cedere alla tentazione di immaginare che la struttura di base della comunicazione pubblicitaria si sia effettivamente evoluta con l’evolversi delle sue tecniche.

Per spiegare meglio questo punto, propongo l’analisi di un esempio che nella nostra ipotetica storia rientrerebbe nel capitolo dedicato alla preistoria: è un volantino (diremmo oggi) eseguito con tecnica xilografica da Erhardt Altdorfer (quasi sicuramente fratello del ben più noto Albrecht) e pubblicizza una lotteria tenutasi a Rostock nel 1516, quasi cinquecento anni fa.

Il foglietto è diviso orizzontalmente in due parti, che sembrano la rappresentazione grafica di un mai sanato dissidio insito nella comunicazione pubblicitaria e su cui negli ultimi decenni si è molto dibattuto: quello fra informazione e emozione. In maniera salomonica l’autore di questo messaggio mette l’informazione nella parte inferiore e l’emozione nella parte superiore del volantino.

Sotto, infatti, vi è l’illustrazione dei premi che si possono vincere in questa lotteria (suppellettili, paramenti, tessuti, gioielli), una semplice elencazione con illustrazioni e didascalie, in cui il massimo di carica emotiva è dato dalla desiderabilità che comunicano gli oggetti stessi, come fossero in una esposizione: è l’effetto della vetrina, su cui tanto contano anche oggi gli stilisti rinunciando così nelle loro pagine alle infinite possibilità offerte dalla pubblicità più articolata.

Sopra invece viene dato campo alla parte emotiva della comunicazione. È prefigurato il giorno stesso della lotteria e la rappresentazione gioca essenzialmente su tre tasti: l’attrazione data dall’intrattenimento, la rassicurazione e l’elemento aspirazionale. Al centro della scena (sembra proprio un teatrino) vi è chi conduce il gioco, un giovane vestito in maniera molto vistosa e elaborata; la xilografia è in bianco e nero, ma possiamo immaginarci i colori sgargianti di questi vestiti, così come possiamo immaginare il biondo splendente della sua capigliatura riccioluta. Egli sta operando con due anfore in cui immette o da cui estrae dei foglietti – la lotteria è in corso. Oggi il suo ruolo sarebbe quello di un presentatore televisivo e, come tale, egli è obbligato a dimostrarsi vivace e divertente. Questo personaggio, dunque, ha funzione di attrazione e di intrattenimento e, a sostenerlo, sulla sinistra della scena vengono introdotti tre suonatori di tromba, anch’essi vestiti in maniera spettacolare e anch’essi portatori di divertimento. Ma, come ogni pubblicitario sa bene, il pubblico, allorché sono in gioco dei soldi, chiede anche garanzie e rassicurazioni e né il presentatore, né i suonatori, con i loro vestiti strani e con le loro acconciature eccessive, sono in grado di tranquillizzare il timoroso spettatore. Ecco che a svolgere questa seconda funzione il pubblicitario cinquecentesco introduce quattro altri personaggi, divisi in due coppie, che circondano il conduttore e ne controllano l’operato: oggi sarebbero dei notai televisivi con i loro assistenti. Anche essi sono vestiti bene, ma con abiti assai seri e semplici e si tratta chiaramente di anziani che temperano con la loro austerità la frivola giovinezza del presentatore. Gran parte del messaggio è già costituito: “Vieni e ti divertitai; ma non temere, ti garantiamo che si tratta di una cosa seria”. Ma non è finita: sull’estrema destra l’autore introduce altri quattro personaggi, con una ulteriore funzione. Siamo all’entrata della sala e un signore maturo, con un registro in mano, controlla gli interessi; vediamo così entrare un anziano abbigliato in modo molto elegante anche se austero come si conviene alla sua età e probabilmente al suo ruolo e, dietro di lui, una coppia il cui fisico opimo e le ricche vesti ci fanno capire che si tratta di personaggi abbienti. Questa ulteriore parte del messaggio dice: “Vieni e così dimostrerai anche tu di appartenere al ceto più ricco e potente”, come oggi certi cioccolatini propongono ai propri consumatori l’illusione di essere invitati dagli ambasciatori e di avere un autista di nome Ambrogio.

Sopra invece viene dato campo alla parte emotiva della comunicazione. È prefigurato il giorno stesso della lotteria e la rappresentazione gioca essenzialmente su tre tasti: l’attrazione data dall’intrattenimento, la rassicurazione e l’elemento aspirazionale. Al centro della scena (sembra proprio un teatrino) vi è chi conduce il gioco, un giovane vestito in maniera molto vistosa e elaborata; la xilografia è in bianco e nero, ma possiamo immaginarci i colori sgargianti di questi vestiti, così come possiamo immaginare il biondo splendente della sua capigliatura riccioluta. Egli sta operando con due anfore in cui immette o da cui estrae dei foglietti – la lotteria è in corso. Oggi il suo ruolo sarebbe quello di un presentatore televisivo e, come tale, egli è obbligato a dimostrarsi vivace e divertente. Questo personaggio, dunque, ha funzione di attrazione e di intrattenimento e, a sostenerlo, sulla sinistra della scena vengono introdotti tre suonatori di tromba, anch’essi vestiti in maniera spettacolare e anch’essi portatori di divertimento. Ma, come ogni pubblicitario sa bene, il pubblico, allorché sono in gioco dei soldi, chiede anche garanzie e rassicurazioni e né il presentatore, né i suonatori, con i loro vestiti strani e con le loro acconciature eccessive, sono in grado di tranquillizzare il timoroso spettatore. Ecco che a svolgere questa seconda funzione il pubblicitario cinquecentesco introduce quattro altri personaggi, divisi in due coppie, che circondano il conduttore e ne controllano l’operato: oggi sarebbero dei notai televisivi con i loro assistenti. Anche essi sono vestiti bene, ma con abiti assai seri e semplici e si tratta chiaramente di anziani che temperano con la loro austerità la frivola giovinezza del presentatore. Gran parte del messaggio è già costituito: “Vieni e ti divertitai; ma non temere, ti garantiamo che si tratta di una cosa seria”. Ma non è finita: sull’estrema destra l’autore introduce altri quattro personaggi, con una ulteriore funzione. Siamo all’entrata della sala e un signore maturo, con un registro in mano, controlla gli interessi; vediamo così entrare un anziano abbigliato in modo molto elegante anche se austero come si conviene alla sua età e probabilmente al suo ruolo e, dietro di lui, una coppia il cui fisico opimo e le ricche vesti ci fanno capire che si tratta di personaggi abbienti. Questa ulteriore parte del messaggio dice: “Vieni e così dimostrerai anche tu di appartenere al ceto più ricco e potente”, come oggi certi cioccolatini propongono ai propri consumatori l’illusione di essere invitati dagli ambasciatori e di avere un autista di nome Ambrogio.

È una costruzione persuasoria che fa parte degli espedienti tipici della pubblicità e che sfrutta l’immedesimazione aspirazionale degli individui pronti ad identificarsi in modelli che considerano superiori, attraverso la mediazione di uno strumento magico di cui possono impadronirsi, cioccolatino o biglietto della lotteria. Certamente le tecniche di comunicazione sono primitive, manca una distribuzione dei pesi che dia una accentuazione maggiore alle parti più importanti del messaggio, manca lo sfruttamento delle potenzialità della parola, manca la memorabilità di un titolo o di uno slogan e, è ovvio, manca la persuasiva verosimiglianza della fotografia. Ma la struttura pubblicitaria c’è già tutta, c’è la promessa materiale, il consumer benefit (i premi), c’è la promessa immateriale (l’identificazione con le classi superiori), c’è la supporting evidence (raffigurazione e descrizione dei premi), c’è la reassurance (i notai).

(1) Sull’argomento c’è comunque un saggio tuttora fondamentale: L.Spitzer, “American Advertising Explained as a Popular Art”, in A Method of Interpreting Literature, Smith College, 1949.

(2) Un primo tentativo di una storia di questo tipo fu abbozzato con grande perspicacia ma scarso sviluppo da Mary Tuck. M.Tuck, “Practical Frameworks for Advertising and Research”, in AA.VV., Esomar Seminar on “Translating Advanced Advertising Theories into Research Reality”, Amsterdam, 1971.

[english]

The year 2000 is now upon us and numerous events are lining up to be celebrated – the end of the millenium (it is not particularly important if the exact date is 2000 or 2001), the Jubilee, or the end of the 20th century which, in itself, has many reasons to be celebrated. Perhaps there are too many things to celebrate, considering that even the Teatro alla Scala, in its bi-millenary season has decided to evoke the development of opera in the 20th century, apparently forgetting that in the year to come also the fourth centenary of the birth of melodrama, an anniversary, if one believes in anniversaries, of the greatest importance, above all for Italy, but it will receive little attention, certainly less than the centenary of Milan A.C.

Another activity which characterises the century coming to an end will also receive little attention, to judge by the total lack of preparations.

If this has been the century of communication, it has equally been that of advertising.

In fact, most of the development of communication, ranging from the radio to journalistic printing, from television to the Internet has been and still is financed by commercial advertising or company communication, as it is more politically correct to call it today.

It is undeniable that this particular branch of communication has deeply interacted with 20th century culture, both at a popular level and in the higher echelons.

It has transformed the nature of landscape, above all the urban landscape and especially the most modern part of urban centres. It has conditioned television languages from their birth, subjecting them to schedules which have to take into account advertising insertions and interruptions. It has revolutionised the form and the nature of magazines, it has modified daily language, enriching it in some cases, impoverishing it in others. It has influenced cinematographic narration by means of a give and take which it is difficult to analyse. It has significantly contributed – sometimes without being aware of it – to the rediscovery of rhetoric (another merit of the century which is dying). It has become popular art, receiving from official culture the same attitude of curious interest and scornful aloofness which other forms of popular art – from the feuilleton to the detective story, from the burlesque to cartoons – had already come up against. It has deeply transformed – political propaganda practices, creating serious ethical and juridical problems. It has made a substantial contribution to the development and progress of socio-demographic research. It has become a formidable weapon in the development of the consumer society. We could go on and on; it is not intended as a list of merits, but only wishes to stress how advertising has co-operated in this century to making of our society that which it is today, for better or for worse.

What is more, this lack of celebration reflects another gap. There still does not exist an authoritative and exhaustive history of the development of advertising, from the earliest Pompeian finds to the authentic advertising explosion of our century. There are many reasons for this.

On the one hand, we might say, as certain advertisers themselves say, that it is a totally unsuitable subject for historical analysis. Advertising production is ephemeral by definition, aimed at responding to the needs of the here and now and destined to disappear once those needs no longer exist. Who cares today about how Camel accompanied the rise of femminism and therefore female smoking, or exploited the affections of the families of soldiers at the front, during the Second World War? This is all long gone by, Camel has to face up to problems of a totally different nature and these concern only its current communicators. The old advertising, at this point would only provide useful clues to investigations about the daily life of other times, or at least study materials for specialists and students of the proliferating schools and universities of communication. Like the pleading of lawyers in the past, they say nothing today, outside the strictly professional sphere.

The most extremist even arrive at adding that advertising is even be worthy of a history, like minor arts1, since it does not amount to such. It is clear from such a negative stance that the more or less declared intention to claim for itself if not a scientificity, at least a prevalence of professional techniques aimed at obtaining a practical result of a persuasive type – once more sustained, above all, by advertisers – in which the component mistakenly passed off as artistic, is no more than a series of rhetorical expedients which can, at most, be inserted into repertories or manuals. The only history possible is therefore a history of advertising techniques and their links with the evolution of the theory of communication (but also in this field little gets done).

On the other hand, we have to take into account the considerable difficulties in getting hold of material which might constitute a documentary and illustrative core for this hypothetical universal history of advertising. These difficulties are mainly the result of the lack of documents from past centuries and the excessive quantity of documents from this century. (It is not by chance that the historiographical examples that we have are almost all from the 20th century and they are particular episodes. In past centuries equally titanic enterprises were carried out in other fields, but such efforts seem basically contrary to the present-day spirit and attitudes and the doubtfulness of whether they are really worth the trouble certainly does not encourage eventual explorers.

We also have to consider the problem of the choice of a perspective, which is necessary to shape and justify the presence and absence of given materials. What is to be stressed? The aesthetic side, provoking the reaction of those advertisers most closest to the persuasive function? The innovative side, leading to an elite presentation which would neglect the great mass of actual production? The economic side, relinquishing a great quantity of episodes of little commercial value but of a high cultural interest? Who has most right to enter this history, the commercial Ferro China Bisleri in which for the first time in Italy and perhaps in the world we see an uxoricide full of gunshots and blood and which has received minor programming – refused by the RAI and only shown in the cinema or the umpteenth presenter convincing the umpteenth housewife to choose her detergent and which is shown again and again ad infinitum, thus conquering a large share of mind slice? Who will have access, the mythical Michele who, criticised by all, determined the success of his whisky and created a new way of considering the entire category, or the famous Genoese comedian who, with a number of extremely amusing spots led to market share of his yoghurt falling? Will “celebrity” dare to define a criterion of selection, according to which however, a David Ogilvy will end up beating a Howard Luck Gossage – much more subtle and innovative than the former? Probably the most convincing way to create such a history – if we ever decide to write one – would be that of letting ourselves be guided by the theories which, step by step, have led production and its transformation and choosing examples from those which illustrate such theories better or more clearly.

However, here also it is necessary, but much easier, to distinguish between false theories, often only dictated by the need for metapublicity and self-celebration, and others known only to the more attentive of specialists but which are more authentically the basis of most production of an era. It is thus be necessary to put into its correct place a star-strategy and fully re-evaluate the attitudes of Fishbein2.

We must also not give into the temptation of imagining that the basic structure of advertising communication has effectively evolved with the evolution of its techniques.

To clarify this point I propose the analysis of an example which in our hypothetical history would go into the chapter dedicated to prehistory. It is a handbill (we would call it so today) carried out, using a xylographic technique, by Erhardt Altdorfer (almost certainly the brother of the much better known Albrecht) and advertises a lottery held in Rostock in 1516, almost five hundred years ago.

This leaflet is divided horizontally into two parts which seem the graphitization of a unresolved conflict inherent in advertising communication and about which in recent decades a great deal of debate has taken place: that between information and emotion. Impartially, the author of this message puts the information in the lower half of the handbill and the emotion in the upper.

Indeed, underneath there is the illustration of the prizes to be won in the lottery (furniture, hangings, textiles, jewels), a simple list with illustrations and captions in which the most emotional impact derives from the desirability which the objects themselves communicate, as if in an exhibition. It is the effect of a shop window, which stylists continue to count on so much, even today, thus relinquishing, on their pages, the infinite possibilities offered by more articulate advertising.

Today they would be television notaries with their assistants. These are also dressed well but in serious, simple clothes and they are obviously elderly people who mitigate, with their austerity, the frivolous youth of the announcer. Most of the message is already there: “Come along and you’ll enjoy yourselves; don’t be afraid, we guarantee that it’s all above board”. But this is not all: on the extreme right the author introduces another four characters, with a further function. We are at the entrance of the hall and a mature man, with a register in his hand, checks the interests; thus we see an old man, dressed very elegantly, albeit austerely, as his age – and probably his role – demands, and behind him, a couple whose portliness and whose wealthy clothes tell us that they are well-off. This further part of the message says: “Come along and you too will prove that you are one of the richest and most powerful class”, just as today, certain chocolates present their consumers with the illusion of being invited by ambassadors to have a chauffeur named Ambrogio.

It is a persuasive construction which is part of the typical expedients of advertising and which exploits the aspirational identification of individuals ready to identify themselves with models they think superior, by means of the mediation of a magical instrument of which they can take possession: chocolate, or lottery tickets.

Certainly the communication techniques are primitive, a distribution of balance is lacking which would place more stress on the most important parts of the message: the exploitation of the potentialities of the word are lacking, the memorability of a title or a slogan and obviously the persuasive verisimilitude of the photograph. But the advertising structure is all there: the material promise, the consumer benefit (prizes), the immaterial promise (the identification with the upper classes), the supporting evidence (representation and description of the prizes) reassurance (the notaries).

(1) On this argument there is an essay which is still fundamental: L.Spitzer, “American Advertising Explained as a Popular Art”, in A Method of Interpreting Literature, Smith College, 1949.

(2) An initial attempt at a history of this type was drawn up with much perspicacity but little development by Mary Tuck. M.Tuck, “Practical Frameworks for Advertising and Research”, in AA.VV., Esomar Seminar on “Translating Advanced Advertising Theories into Research Reality”, Amsterdam, 1971.

Pubblicato per la prima volta in: Nota Bene. I linguaggi della comunicazione/Communication languages, Anno 1 – N. 1, 1999, Fausto Lupetti Editore.