Il tasto giusto

The right bottom

Intervista a Stefano Bollani

Esiste un istinto musicale innato?

Tutti hanno talento musicale, la differenza sta nel fatto che alcuni riescono a tirarlo fuori ed esercitarlo con maggiore facilità. Al di là di programmi di insegnamento più o meno validi, esistono buoni insegnanti e cattivi insegnanti. C’è chi plasma l’allievo a propria immagine e somiglianza, disinteressandosi completamente della sua personalità. Ricordo che a nove anni, ho preso coraggio e ho chiesto alla mia maestra di musica classica se mi insegnasse a suonare Pianofortissimo di Renato Carosone. Molti docenti mi avrebbero messo a tacere, liquidando quel brano come una banale canzonetta senza dignità che non aveva niente a che fare con la musica ‘seria’. Lei invece non ha mostrato pregiudizi e mi ha fatto suonare una canzone che non conosceva neanche. Quasi sempre la didattica della musica segue una rigida impostazione nel rispetto di regole prestabilite, senza preoccuparsi degli interessi e delle inclinazioni degli studenti. Il conservatorio, come testimonia il nome, è una realtà assolutamente conservatrice. Ci sono cose che ritengo aberranti: sono convinto che molti bambini proseguirebbero lo studio della musica se non incontrassero per prima cosa sulla loro strada il dogma del solfeggio. È un’assurdità pretendere di insegnare a un bambino come si chiamano, si scrivono e si leggono correttamente le note, prima ancora che abbia preso in mano uno strumento e ne abbia scoperto il suono. Sarebbe come insegnare al proprio figlio, che ancora non sa parlare, la scrittura della parola ‘albero’ senza che ne abbia visto almeno uno, quantomeno in foto o in disegno. La musica è un linguaggio e, come nell’apprendimento del linguaggio verbale, lettura e scrittura andrebbero insegnate a coloro che hanno già iniziato a parlare. Come avviene in tante altre culture non occidentali, bisognerebbe che le persone incontrassero la musica prima di tutto suonandola. Noi invece abbiamo abolito questo primo approccio diretto e spontaneo alla musica: autorizziamo a parlare soltanto chi sa leggere e scrivere. Siamo sopravvissuti in tanti a una simile didattica della musica, ma sono convinto che abbia prodotto i suoi danni: molte più persone, anche se non sarebbero diventate comunque dei musicisti professionisti avrebbero potuto avere una relazione più profonda e consapevole con il mondo della musica.

Quanto istinto e quanta strategia c’è nel musicista jazz?

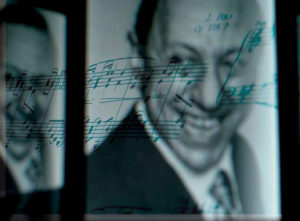

Intendo il jazz come un’estetica che trova nell’improvvisazione la strategia per rinnovare, attraverso l’istinto, una struttura data. Al di là di qualsiasi ideale di perfezione, vive soprattutto in relazione al mood del momento. L’improvvisazione, pur non nascendo nel jazz, ne è l’autentica prerogativa. Anche se al conservatorio non viene raccontato, improvvisavano già i musicisti barocchi, sebbene in maniera più limitata e in sudditanza di determinate categorie estetiche. Di fatto, nello studio della musica classica si è deciso di bandire l’istinto unicamente a favore della strategia, quella di definire ogni dettaglio dell’interpretazione di un brano assolutamente prima della sua esecuzione. Si insegna a suonare seguendo accuratamente un copione prefissato, senza lasciare spazio all’istinto musicale del momento. Ma, guarda caso, i grandi musicisti classici di solito non hanno mai mostrato gran sintonia con i precetti dell’accademia. Ed è proprio questa estetica dell’imperfezione il vero contributo del jazz al Novecento. L’imperfezione non deve essere rinnegata perché è sintomo di ricerca. Il jazz non vuol essere celebrazione di una forma compiuta. Quando l’obiettivo è quello di perseguire un’interpretazione definitiva e raggiungere una forma perfetta, non c’è spazio per i rischi dell’improvvisazione e l’errore. E siccome un’esecuzione interamente soddisfacente non c’è mai, la sala di registrazione diventa allora uno strumento strategico per catturare le note giuste, assicurare i passaggi desiderati e aderire quanto più possibile alla forma idealizzata. E così un’incisione di sette minuti può contare oltre trecento tagli da parte del tecnico del suono. Evan Eisenberg, nelle pagine del libro L’angelo con il fonografo, spiega molto bene come l’avvento del disco abbia cambiato il modo di comporre e concepire la musica, anche quella classica. Glenn Gould è un vero stratega del lavoro in studio e della volontà di lasciare incisioni dove niente è lasciato al caso. Se l’intento è quello di firmare un’interpretazione di Bach che corrisponda il più perfettamente possibile alle decisioni stilistiche prese, è ovvio che la presenza del pubblico può essere solo di disturbo e che l’imprevisto come l’istinto debbano essere esclusi. Il melting pot che è all’origine del jazz (e dell’America tutta) ha fatto sì che diventasse quasi subito non solo un genere musi- cale ma un vero e proprio linguaggio aperto utilizzato dalle culture più diverse. Il jazz ha influenzato in maniera più o meno dichiarata tutte le arti, anche quelle che sembrano non essersene accorte. Se la beat generation di Allen Ginsberg e Jack Kerouac si è ispirata direttamente al linguaggio jazz, anche esperienze apparentemente distanti come le rappresentazioni del Living Theatre o l’action painting di Pollock ne ripropongono lo spirito. Un linguaggio che ha però una grammatica e delle regole che possono essere insegnate e apprese. Se c’è una cosa che il jazz ha sempre cercato di fare è quella di coniugare istinto e strategia. Nonostante la convenzionalità dei media lo descriva solo e soltanto come istinto allo stato puro. Leggenda vuole che i più grandi musicisti jazz siano pressoché analfabeti, con storie di emarginazione sociale e povertà, insomma, dei selvaggi miracolati dalla musica. Questa mistificazione della realtà ha portato a far diventare paradigmatici aneddoti come quello di Bix Beiderbecke incapace di leggere uno spartito, di Ella Fitzgerald geniale autodidatta che non ha seguito una sola lezione di canto o di Freddie Keppard che non ha mai inciso un disco per paura che gli altri potessero copiare il suo stile. Un po’ come il mito di Mozart bambino prodigio e genio senza regole. In realtà molti di questi artisti la musica la conoscevano e, soprattutto, la pensavano. Neanche icone della generazione maudit come Chet Baker e Charlie Parker possiamo pensare salissero sul palco come tossicomani invasati dal demone del jazz e improvvisassero guidati da un’istinto animale. I due sapevano perfettamente cosa e come suonare, il punto è che non lo sapevano spiegare in termini musicali, o meglio nei termini musicali canonici della musica europea. Come non dobbiamo cadere nella presunzione di affermare che c’è un solo modo di conoscere la vita, così non dobbiamo credere che esista un solo modo di pensare la musica. Parker non ha mai teorizzato in vita quali fossero le scale ben definite che in maniera del tutto consapevole utilizzava, ma individuate dai suoi adepti sono poi diventate la grammatica basilare del jazz moderno.

Ancora oggi il jazz detiene il primato di linguaggio musicale più libero?

Alla morte di qualcuno che in vita ha fatto cose importanti si erige un monumento alla sua memoria, anche se magari era il primo a scagliarsi contro le celebrazioni. Spesso nella storia della musica i musicisti più anti-accademici sono poi diventati emblemi intoccabili della musica accademica. È anche il caso di molti jazzisti che, mediaticamente e musicalmente, sono diventati paradigmi assoluti del jazz. Gli ultimi capolavori di riferimento incisi da grandi maestri come Wayne Shorter appartengono agli anni Novanta. Dopodiché è difficile trovare personalità simili; anche i musicisti più bravi si rifanno nella grammatica e nell’estetica a un determinato periodo storico rendendo il jazz un genere inevitabilmente accademico. È vero che improvvisano, ma continuano a improvvisare con le regole degli anni Cinquanta: stanno eseguendo una performance filologicamente corretta, come se stessero eseguendo una ballata di Chopin. Pensare come Wynton Marsalis, direttore del prestigioso Lincoln Center, che al jazz debba essere riconosciuto ufficialmente lo status di nuova musica classica (con regole e grammatiche scritte una volta per tutte) significa, di fatto, privarlo di vitalità rinnegandone le evoluzioni presenti e future. In altre parole, così si va a scegliere un momento storico del jazz e si decide che da lì in poi, il jazz è morto. Un errore in cui, prima o poi, tutti i cosiddetti ‘puristi’ del jazz incorrono. Ma se il jazz non è un genere musicale ma un linguaggio, individuarne la data di morte non ha senso. È una realtà multiforme che intelligentemente si è insidiata in tante altre realtà, anche se in maniera non dichiarata, e proprio per questo sopravvive e non si lascia incasellare in una ‘storia del jazz’ scritta a suon di correnti musicali ed eroi.

Contraddizioni in termini: un’improvvisazione è tanto convincente da sembrare composizione scritta e un’esecuzione è tanto autentica da sembrare illuminazione del momento?

Un giorno ascoltando la radio ho sentito suonare al piano un brano che non avevo mai sentito: poteva essere Keith Jarrett che improvvisava dal vivo o un musicista classico che eseguiva uno spartito; proseguendo con l’ascolto mi sono convinto che si trattasse della prima ipotesi: chiunque fosse, stava suonando trasmettendo un’impressione di autentica spontaneità. Soltanto alla fine ho scoperto di essere stato tratto in inganno: quello che avevo ascoltato erano i Preludi di Debussy eseguiti da Jörg Demus. Anche se in questo caso, parte dell’inganno era stato teso – ahimé – dalla mia ignoranza, realizzare l’illusione della spontaneità non richiede necessariamente che istinto e strategia siano mascherati. Un attore che recita un’opera famosissima come l’Amleto non può mentire con il pubblico sulla spontaneità delle sue battute: lo spettatore già le conosce prima ancora che siano pronunciate. Tuttavia anche nella consapevolezza che si tratta di finzione perché tutto è già scritto su un copione, un bravo attore convince e commuove. Anche in musica non possiamo assistere stupefatti all’esecuzione di brani noti, abbiamo già delle aspettative e anticipiamo mentalmente il divenire del brano. Più è conosciuta l’opera che viene recitata o suonata, maggiore è la difficoltà dell’interprete. L’impressione che Demus mi aveva trasmesso era quella di un musicista che stava componendo sul momento, che esitava nel procedere scegliendo di volta in volta la strada da seguire. Di fatto, invece, si trattava di scelte calibratissime concepite a tavolino da un compositore straordinario che oltre mezzo secolo fa aveva fissato sul pentagramma il divenire di ogni nota. Ma l’applauso va anche a chi, improvvisando veramente, riesce a costruire una cosa talmente bella formalmente da non poter pensare che sia stata improvvisata. Questo forse è il vero colpo di genio, il risultato massimo della giusta combinazione di istinto e strategia. E il merito dei grandissimi musicisti è che non te le fanno pesare, non ti fanno intuire la complessità dello sforzo creativo del momento. Spesso mi viene chiesto a che cosa io pensi quando sto suonando: semplicemente, penso alla musica. Valuto quale accordo fare, che direzione intraprendere. È proprio perché sto improvvisando che devo pensare bene a ogni dettaglio musicale di quello che sto per fare. A volte subentrano degli automatismi delle mani, altre vengo trascinato dalla frase di un musicista che suona con me, arrivando a cambiare totalmente il discorso che mi ero prefigurato. Improvvisare non significa ignorare le regole, tutt’altro. La vera libertà è quella di conoscerle ma applicarle in maniera sempre diversa e, talvolta, sovvertirle. Una libertà che non promette la certezza del risultato e che, dunque, può anche spaventare.

La volontà di rileggere e improvvisare su una composizione trova a volte qualche ostacolo obiettivo?

Certa musica funziona proprio in virtù della sua forma. Ad esempio, inizialmente avevo pensato il mio disco Piano solo come un omaggio interamente dedicato a Prokofiev, ma poi ho rinunciato, lasciando una sola improvvisazione intorno a un tema del grande compositore sovietico. Gran parte della musica classica del Novecento è costruita su architetture ponderatissime in cui la melodia ha un ruolo marginale: manca la materia prima per poter sviluppare una variazione sul tema. Scomporre e ricomporre la struttura significa sconfessarne l’essenza. Una cellula melodica individuata in Mozart consente invece esercizi sorprendenti. E poi mi scontro sempre con la difficoltà di suonare e improvvisare sui brani che mi piacciono di più. In questo non tengo fede a quello che è invece il mio istinto dichiarato: risuonare una musica non per renderla migliore ma, semplicemente, diversa. Ma con certi pezzi musicali vengo sopraffatto dalle manie di perfezione e comincio a ripetermi che è inutile toccarli perché l’atmosfera era già perfetta, il suono del disco era già quello giusto…e così, paradossalmente, mi ritrovo a improvvisare su una ‘canzonetta’ di Riccardo Del Turco e raramente sul repertorio dei miei adorati Beatles, perché magari non riesco a immaginare i loro brani diversi da come sono, da come li ho amati.

Esiste un valore aggiunto nell’identità culturale raccolta dal jazz italiano?

Il jazz italiano di oggi sfugge a una sola definizione: presenta più anime, dalle correnti legate al formalismo classico ai musicisti memori della tradizione delle bande paesane. Così come esistono molte definizioni per il jazz europeo, territorio di culture molto diverse tra loro. In generale, si è deciso che l’apporto principale è l’algidità, una caratteristica che in parte è conseguenza della classicità attribuita al jazz in un continente storicamente così ricco di tradizione musicale. Una concezione che però tradisce il pregiudizio che contrappone un’adeguata preparazione accademica e intellettuale alla preparazione approssimativa e alla presunta ignoranza diffusa dell’America dei neri. Ma se il jazz europeo può essere definito più intellettuale è per altri motivi: quasi da subito ha lasciato i locali da ballo per essere suonato nei teatri e questo, inevitabilmente, ha influenzato anche l’atteggiamento dei musicisti. E sebbene il catalogo di una casa discografica prestigiosa e rappresentativa come la ECM sia molto variegato, l’immagine del jazz europeo contemporaneo che arriva presso il grande pubblico è parziale: quella della purezza formale evocata dalle incisioni di musicisti nordici e scandinavi. In effetti, da oltre quarant’anni, Manfred Eicher dirige l’etichetta di Monaco di Baviera con una strategia ben precisa: sviluppare un vero e proprio progetto artistico a cui, di volta in volta, prendono parte i diversi musicisti in catalogo. Le scelte di produzione non rispondono a necessità commerciali, ma alle istanze di una visione autoriale. E così le uscite discografiche a marchio ECM non vogliono essere una rassegna esaustiva del jazz dei nostri giorni, ma l’opera riconoscibile di un artista guidato dal proprio gusto musicale. Il jazz più intellettuale di tutti è senza dubbio quello francese: i primi ad ascoltare jazz in Europa sono stati grandi protagonisti della scena intellettuale come Sartre e Boris Vian, e quando poi è diventato la colonna sonora della nouvelle vague di Truffaut e di Godard ha acquisito lo status di un genere certamente conosciuto e riconoscibile, ma non popolare. In Italia per molto tempo non è stata neanche una musica di élite perché censurata dal Fascismo come musica negroide, e soltanto più tardi pochissimi artisti lo hanno amato, ne hanno subito l’influenza, ne hanno parlato. In me spesso fa capolino un’idea del jazz vicina a quella delle sue origini: una musica nata nella strada da un popolo emarginato, con una spontanea visione di ‘collettivo’ che arriva direttamente dall’Africa. Una musica inizialmente suonata nei postriboli. Con il jazz si ballava, si faceva l’amore e anche si sparava. Una musica che continua anche ad essere spettacolo, entertainment, termine intraducibile se non con ‘intrattenimento’, termine sotto sotto piuttosto spregiativo e che rimanda al piano-bar.

Sei applauditissimo interprete degli standard di Gershwin, ma anche sceneggiatore delle strisce che hanno per protagonista il tuo alter ego a fumetti, Paperfano Bolletta, sulle pagine di Topolino. Un musicista fuori dagli schemi con il guizzo della migliore tradizione cabarettistica italiana. A dispetto di ogni strategia di immagine?

Fin da piccolo sono sempre stato un po’ giullare e santimbanco, è la mia personalità. Alcuni pensano che alla base delle mie scelte ci sia la volontà di sfuggire dalle definizioni. In realtà a me sembra di fare sempre e comunque la stessa cosa: comunicare, e con entusiasmo. Quando dopo essermi diplomato al Conservatorio Cherubini di Firenze, grazie alla stima di Enrico Rava, sono potuto uscire dal tunnel pop degli anni passati da turnista dedicandomi con sincerità a quello che mi piace fare veramente… Quando ho scritto un romanzo o fatto parodie in una trasmissione televisiva… quando gioco con il mio pubblico o conduco una trasmissione radiofonica lo faccio utilizzando sempre quello che credo essere un solo linguaggio. Il bello del mio lavoro è che, ormai da molti anni, posso decidere liberamente di fare quello che voglio, senza pormi problemi di immagine e lasciandomi guidare dall’istinto e dal piacere.

[english]

Interview with Stefano Bollani

Is musical language an innate instinct?

Everyone has a talent for music, the difference is that some manage to draw it out and practice it with more ease. There are good teachers and bad teachers, apart from the syllabus, which might be more or less valid. There are those who mould the student into their own image and resemblance, entirely ignoring the student’s personality completely. I remember that when I was nine I asked my classical music teacher to teach me to play Pianofortissimo by Renato Carosone. A lot of teachers would have just ignored me, passing this piece off as a silly song devoid of dignity which had nothing to do with ‘serious’ music. However, she had no any prejudice about it and she got me playing a song which she probably didn’t even know. Almost always, music teaching is tightly structured with respect to pre-established rules, and does not bother with the interests and inclinations of the students. The academy of music, as its name in Italian – conservatorio – suggests, is very conservative body indeed. There are things I consider aberrant, I am sure that many children would take up studying music if they didn’t come up against the dogma of solfeggio at the beginning. It is absurd to expect a child to learn what notes are called, how they are written and how they are to be read – correctly, even before they have come into physical contact with an instrument and discovered the sound it makes. It would be like teaching one’s own child, who has not even begun talking, how to write and pronounce the word ‘tree’ before he has even seen one. Music is a language and as in the learning of verbal language, reading and writing should be taught to those who have already begun to speak. As happens in so many other non-western cultures, we need people to encounter music above all by playing it. We, on the other hand, have abolished this first direct, spontaneous approach to music and I am convinced that this has damaged us. Many more people, even though they wouldn’t have become professional musicians, would have been able to have had a deeper relation with, and more awareness of, the world of music.

How much instinct and strategy is there in the jazz musician?

I see jazz as an aesthetics which finds its strategy for renewal of a given structure in improvisation, by means of instinct. Separate from any ideal of beauty and necessity, only the relation to the mood of the moment. Improvisation, even though it did not begin with jazz, is its authentic prerogative. Though they don’t tell you this at the academy, Baroque musicians were already improvising, even though in the sphere of a limited number of bars and in subjection to given aesthetic categories. In fact, in the study of classical music the decision was taken to banish instinct in favour of strategy, that of defining every detail of the interpretation of a piece before its execution. One teaches to play, following accurately a prearranged script, leaving nothing to the musical instinct of the moment. But paradoxically the great classical musicians have never, on the whole, been in tune with the precepts of the academy. Jazz does not wish to be the celebration of a finished form. And it is just this aesthetics of imperfection which is jazz’s real contribution to the 1900s. Imperfection which should not be denied because it is a symptom of research. When the objective is that of pursuing a definitive interpretation and achieving a perfect form, there is no room for the risks of improvisation and the error. Since a completely satisfying execution does not exist, the recording studio becomes a strategic instrument for capturing the right notes, assuring the desired passages and adhering as much as possible to the idealised form. Thus, a seven-minute recording might undergo three hundred cuts by the sound engineer. Evan Eisenberg, in his book L’angelo con il fonografo explains very well how the advent of the record changed the way music was composed and conceived, classical music too. Glenn Gould is an authentic strategist, concerning work in the studio and the desire to make recordings in which nothing is left to chance. If the aim is to offer an interpretation of Bach, which most corresponds to the stylistic decision taken, it is obvious that the presence of the public can only be a disturbance and that the unexpected as instinct has to be excluded. So the melting pot, which is the origin of jazz (and the whole of America) led to it becoming, almost immediately, not only a musical genre but nothing less than an open language in itself, used by a variety of cultures. Jazz influenced all the arts in more or less obvious ways, even those which seem not to have noticed. While the beat generation of Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac was directly inspired by jazz, experiences which were apparently distant, like the representations of the Living theatre or Pollock’s action painting, re-proposed its spirit. A language however, which has a grammar and rules which can be taught and learned. If there is one thing that jazz has always tried to do it is to conjugate instinct and strategy, despite the conventionality of the media in describing it only as an instinct of a pure nature. This mystification of reality has led to false legends, for example about Bix Beiderbecke who couldn’t read sheet music or Ella Fitzgerald as a self-taught genius who never took a single singing lesson or Freddie Keppard who never recorded because he was afraid others might copy his style. In actual fact, all these artists knew and above all thought about music. Not even icons of the maudit generation like Chet Baker and Charlie Parker. Drug addicts getting up on the stage possessed by the jazz demon and improvising. Both knew perfectly well what and how to play, the point is that they did not know how to explain, in musical terms or rather in the canonical musical terms of European music. Just as we shouldn’t fall into the trap of presuming that there is only one way of knowing about life, we must not believe that there exists only one way of thinking about music. Parker never theorised in his life about the well defined scales which he, unaware, was using but once singled out by his followers, they later became the basic grammar of modern jazz.

Does jazz still today hold the record for the freest musical language?

When someone who in life did important things dies, a monument is dedicated to his memory even though he would have been the first to rebel against such celebrations. Often in the history of music, the most anti-academic musicians then became untouchable emblems of academic music. This is also the case with many jazzmen who, in media terms and musically have become absolute paradigms of jazz. The latest masterpieces recorded by great musicians like Wayne Shorter belong to the 1990s. After which it is difficult to find such characters. Even the most talented musicians look to a certain historical period in the grammar and aesthetics, making jazz an inevitably academic genre. It is true that they improvise, but they continue to improvise following the rules of the 1950s. They are executing a philologically correct performance as if they were playing a ballad by Chopin. To think, like Wynton Marsalis, director of the prestigious Lincoln Centre, that Jazz has to be officially acknowledged with the status of new classical music (with rules and grammars written once, to be used by all) actually means depriving it of vitality, denying it present and future evolution. In other words, we go and choose a historical moment in jazz and decide that from then on jazz is dead. A mistake which sooner or later all the so-called jazz ‘purists’ risk making. But if jazz is not a musical genre but a language, singling out the date of death has no sense. It is a multiform reality which has intelligently inserted itself in many other realities, though without declaring it and just for this it survives and does not let itself be pigeonholed in a ‘history of jazz’ written to the beat of musical currents and heroes.

Contradictions in terms: is an improvisation so convincing as to seem a written composition and is an execution so authentic as to seem illumination of the moment?

One day, while listening to the radio, I heard a piece on piano I had never heard before, it could have been Keith Jarret improvising live or a classical musician following a score – I kept on listening and I became convinced that it was the first, whoever it was, playing and transmitting an impression of authentic spontaneity. Only at the end did I discover that I had been tricked since I had in fact been listening to the Preludes by Debussy played by Jörg Demus. Even though in this case , part of the trick was due – alas – to my ignorance, achieving the illusion of spontaneity does not necessarily require instinct and strategy to be masked, An actor doing a famous play like Hamlet cannot lie to the public about the spontaneity of his lines, the spectator already knows them before they are pronounced. And yet, even in the awareness that we are dealing with fiction because everything is written in a script, a good actor convinces and moves. In music too we cannot stand by amazed at the execution of known pieces, we already have expectations and we see before, mentally, the becoming of the piece. The more the work being recited or played is known, the greater is the difficulty of the performer. The impression which Demus left was that of a musician who was composing at that moment, who was hesitating in proceeding, choosing one at a time the paths to follow. In fact, they were well-balanced choices conceived theoretically by an extraordinary composer who, more than half a century ago had fixed on the musical staff the becoming of every note. But we should also applaud whose who, by really improvising, manage to construct something so beautiful, formally, that we do not think of it as improvised. This is the real stroke of genius, the greates result of the right combination of instinct and strategy.

And it is thanks to the talent of the great musicians that you do not feel it as a burden, they do not let you realize the complexity of the creative strength of the moment.

Does the desire to re-read and improvvise on a composition sometimes come up against certain objective obstacles?

Some music works precisely in virtue of its form. For example, initially I thought of my Piano solo as a homage dedicated entirely to Prokofiev, but then I decided to let it go, leaving only one improvisation on a theme of the great Soviet composer. Most of the classical music of the 1900s is built upon a well thought out architecture in which melody has a marginal role. The raw material with which to develop a variation on a theme is missing. Breaking down and recomposing the structure means disavowing its essence. Whereas a melodic cell singled out in Mozart allows us surprising exercises. And then I’m always coming up against the difficulty of playing and improvising on pieces which I like best. Here, I am not faithful to that which is my declared instinct, playing music again not to make it better but simply different. But with certain musical pieces I am overwhelmed by the mania for perfection and I begin to repeat to myself that that it is useless to touch them because the atmosphere was already perfect, the sound of the record was already right…and thus, paradoxically, I find myself improvising on a ‘canzonetta’ by Riccardo Del Turco and seldom on the repertory of my beloved beatles, because maybe I can’t imagine their pieces being different to what they are, to how I loved them.

Is there an added value in the cultural identity taken up by Italian jazz?

Italian jazz nowadays eludes only one definition: it presents a number of souls, ranging from the currents linked to classical formalism to the musicians mindful of the traditions of small town bands. Just as there are many definitions for European jazz, a territory of cultures with big differences between them. In general, what was decided on was that the main contribution is algidity, a characteristic which is partially a consequence of classicality attributed to jazz in a continent historically so rich in musical traditions. A conception which, however, betrays the prejudice which counterpoises an adequate academic and intellectual preparation to the approximate preparation and the presumed ignorance spread in America by negroes. But while European jazz can be defined as more intellectual and above all for other reasons – almost immediately it left the dance halls to be played in theatres and this inevitably, influenced the attitude of the musicians too. And though the catalogne of a prestigious, representative recording label like ECM has a lot of variety, the image of contemporary European jazz which gets to the public at large is partial. That of formal purity evoked by the recordings of Nordic and Scandinavian musicians. In fact for more than forty years Manfred Eicher has headed the Munich label with a very clear strategy in mind, i.e., developing a veritable artistic project in which, one at a time, the different musicians in the catalogue take part. The production choices do not necessarily respond to a commercial need but to the demands of an authorial vision. And so ECM record releases do not wish to be an exhaustive collection of the jazz of our times, but the recognisable work of an artist guided by his own musical taste. Clearly, the most intellectual of all jazz is French. The first people to listen to jazz in Europe were great intellectuals like Sartre and Boris Vian and when it became the soundtrack of the nouvelle vague of Truffaut and Godard it became, it is true, a well-known, but not popular, genre. In Italy for a long time it was not even music for the elite because it was censured by Fascism as Negroid and only later, a very few artists like Modigliani loved it, underwent its influence, spoke of it. Often the idea of jazz which is dear to me is much closer to that of the origins, a music born in the streets from an emarginalised people with a spontaneous vision of the ‘collective’ which arrived directly from Africa. Accompanied by jazz one danced, one made love one even fired guns. A music which also continues to be spectacle, entertainment, impossible to translate into Italian, a term which deep down is rather derogatory, ‘piano bar’ springs to mind.

You are much admired as an interpreter of Gershwin’s standards but also as scriptwriter of a comic, in which your alter ego is the main character, Paperfano Bolletta in Topolino. A mould breaking musician with the sparkle of the best Italian cabaret tradition. In defiance of every image strategy?

Since I was small I have always been something of a jester and acrobat, it’s my personality. Some think that behind my choices there is a desire to escape definitions. Actually, it seems to me I’m always doing the same thing, communicating, with enthusiasm. After graduating from the Conservatorio Cherubini in Florence, thanks to the esteem of Enrico Rava, I was able to emerge from the pop tunnel of the years spent as session musician, dedicating myself sincerely to that which I really like…When I was writing the novel or when I do parodies of a television broadcast …when I play with my public or present a radio programme, I always do it using that which is I think is a single language. The nice thing about my work is that now, after many years, I can decide freely to do what I want to do, I don’t have to worry about my image and I let myself be guided by instinct and pleasure.

(Tratto da/from: NB. I linguaggi della comunicazione, Shake the wor(l)ds, N.1, Anno II, Logo Fausto Lupetti Editore, Milano 2010.)